Keywords: local content, oil and gas, offshore petroleum, local content regulations in extractive industry, Ghana’s local content regulation, Ghana upstream petroleum sector, L.I. 2204, African petroleum sector.

Abstract

Enactment of Ghana’s Petroleum (Local Content and Local Participation) Regulations, 2013 (L.I. 2204) was intended to regulate the percentage of local products, personnel, financing, and goods and services rendered within Ghana’s upstream petroleum industry value chain. L.I. 2204 was sanctioned to facilitate the establishment of a quota of indigenous employees within Ghana’s upstream petroleum industry. A gap between the requirements of L.I. 2204 and professional practice is evident even after the inception of Ghana’s upstream oil and gas industry six years ago. The specific problem addressed in this study is the lack of measurement of the prevailing human resource local content in Ghana’s oil industry, which has not been matched up to the requirements of L.I. 2204. Furthermore, it has not been established whether the training acquired by indigenous Ghanaians seeking jobs in Ghana’s oil fields affects the prevailing local content in its upstream petroleum industry. This paper examines the extent of differences between the prevailing human resource local content and the requirements of L.I. 2204 in Ghana’s upstream petroleum industry. Consequently, the measurement and establishment of the prevailing human resource local content would provide indigenous Ghanaians with knowledge on the current local content compared with the requirements stipulated by L.I. 2204.

Introduction

Over the past 9 years, African governments have enacted laws aimed at improving the livelihoods of indigenous people by streamlining the employment of foreign nationals within extractive industries, thereby mitigating agitations around local unemployment. Despite the existence of a local content and local participation regulation in Ghana (L.I 2204), there are growing concerns about the lack of available jobs for indigenous people in the country’s upstream oil and gas fields. Based on a critical examination of livelihood capitals and the job situation, Ramos-Mrosovsky (2012) argued that jobs related to oil production that have been promised by the government are simply not available. Because of the capital intensiveness of the upstream petroleum sector, only a few highly skilled professionals acquire employment within this sector (Otoo, Osei-Boateng, & Asafu-Adjaye, 2009). Moreover, these highly skilled professionals are mostly foreign nationals.

Atsegbua (2012) and Gray (2013), who studied LCPs in Nigeria and Brazil, respectively, emphasized the need to investigate the local content aspect of oil production in developing countries. Moreover, the pragmatism of these local content regulations governing the employment of foreigners within extractive industries is typically questionable. Egwaikhide and Omojolaibi (2014) claimed that the steady growth in extractive industries recorded for African countries has not provided the promised jobs, leading to local agitations. Moreover, the efficiency of LCPs has revealed that creating business prospects and job opportunities, and establishing special quota arrangements to benefit indigenes in oil-producing countries, were critical considerations (Ugwushi et al., 2011). Jensen and Tarr (2008) noted that during oil and gas field concession negotiations, the local content and local participatory aspect constituted an integral part of the negotiations. Though L.I. 2204 was enacted by the government to address the local participatory aspect of Ghana’s oil production, the lack of jobs in the oil fields has caused frustration among indigenous Ghanaians.

Overview of Ghana’s Upstream Oil and Gas Sector

The emergence of Ghana’s upstream petroleum sector dates back to 1896 when hydrocarbon exploration began in the western region of Ghana following the discovery by explorers of inland petroleum seepages. Between 1896 and 1957, shallow exploration wildcat drilling was conducted in 21 unproven areas. Of these areas, most of the shallow wells contained hydrocarbons (GNPC, 2014). Within the offshore environment, Ghana’s first commercial well was drilled at Saltpond Basin in 1970. This well subsequently yielded commercial quantities of oil and gas, peaking at 4,800 barrels of oil per day (bopd) in 1978 (GNPC, 2014). From 1978 up to 2007, when significant quantities of oil and gas were discovered, Ghana’s upstream petroleum sector was quiescent. In 2007, the discovery of substantial deposits of oil and gas at the Jubilee field led to oil production that reached a significant scale in November 2010 (GNPC, 2014). The successful launching of oil extraction in the Jubilee field, which produces an average of 110,000 bopd, attracted other multinational petroleum companies to Ghana, resulting in a vibrant upstream oil and gas industry. Consequently, to increase local participation in the upstream petroleum industry, L.I. 2204 was ratified in 2013.

In compliance with L.I. 2204, both Tullow and ENI employ locals. In turn, the operators have employed foreign petroleum companies that are oil and gas product service line providers such as Halliburton, Baker Hughes, MODEC, and Schlumberger.

Operational Structure of Ghana’s Upstream Petroleum Sector

Ghana’s upstream petroleum sector is ar representative of the organizational structure of offshore oil and gas industries worldwide. There are three categories of staff: management, technical, and other staff. The main departments, which are subsea, topsides, engineering, operations, procurement, accounts, human resources, and administration, are interlinked within the supply chain that ensures oil and gas production. The management staffs are the heads of the various departments. The technical workforce includes engineers, technicians, geoscientists, and chemists. The other staffs work in the areas of procurement, accounts, human resources, and administration. The data for this study related to these categories of human resource personnel.

Overview of Ghana’s Petroleum (Local Content and Local Participation) Regulations, 2013 (L.I. 2204)

Oil and gas production forms the backbone of the economies of developing countries that are endowed with natural resources. According to Tordo, Tracy and Arfaa (2011), exploitation of natural resources in developing countries plays a key role in maintaining the economic sustainability of these countries. To improve the livelihoods of the indigenes in petroleum producing countries, there is a need to empower locals to take charge of the petroleum sector. LCPs date back to the early 1970s when they were first introduced in the North Sea context as a means of restricting imports and enabling states to directly intervene in the petroleum sector (Tordo, Warner, Manzano, & Anouti, 2013). Over time, they have evolved in accordance with the benefits that governments seek to reap from the exploited mineral resources (Tordo et al., 2013). L.I. 2204, which was aimed at providing indigenous Ghanaians with control over the upstream petroleum sector, came into full effect on February 19, 2014 (IOGIRC, 2015). As stated by the Petroleum Commission of Ghana (2015), L.I. 2204 was formulated to promote job creation and maximize and retain value addition relating to goods and services, local expertise, and financing and business within the petroleum sector value chain in Ghana. In support of this aim, L.I. 2204 seeks to build local capacities within the Ghanaian oil and gas sector value chain through expertise development, skills and technology transfers, and active research and development programs (Enterprise Development Center Ghana, 2013). The objectives of the L.I. 2204 regulation include the following:

- To attain a minimum level of employment of indigenous Ghanaians, as well as in-country expenditure on goods and services within the oil and gas sector value chain.

- To improve the capability and global competitiveness of domestic businesses.

- To sustain economic development through the creation of petroleum and associated supportive industries.

- To achieve and sustain a certain degree of control by indigenous Ghanaians as stakeholders in petroleum development initiatives.

L.I. 2204 covers three main areas: human resources, procurement of goods and materials, and services provided by local companies. This study focused on the regulation of human resources under L.I. 2204.

Participation of Indigenous Ghanaians in Ghana’s Offshore Petroleum Sector

The International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association (IPIECA) has defined local content as value added to a host nation through the training and employment of indigenous people, as well as development and procurement of supplies and services locally. Oil and Gas IQ (2015) has an alternative definition of local content as the percentage of manpower and materials that are acquired indigenously, with the sole aim of fostering the development of a local skills base. Under Ghana’s local content and local participatory regulation, L.I. 2204, local content is defined as the percentage or quantum of personnel, locally produced materials, financing, and goods and services rendered within the oil and gas industry value chain that can be measured in monetary terms. In the L.I. 2204 regulation, local participation specifically relates to the level of equity owned by local citizens in the oil and gas sector. Mwakali and Byaruhanga (2011) defined local content in the context of the Ugandan petroleum sector as the use of local materials and services as a means of adding value to Uganda. Based on an analysis of the above definitions, the sole aim of local content would seem to be to improve the livelihoods of the indigenes of a nation whose natural resources are being exploited by foreign companies extracting minerals. Local content is thus designed by the governments of countries richly endowed with natural resources to improve per capita incomes.

Types of Human Resource Local Content Policies

Tordo et al. (2013) noted that petroleum producing countries have adopted a variety of LCPs aimed at improving the number and quality of indigenes employed by foreign oil and gas companies. Esteves et al. (2013) further pointed out that WTO members categorized as least developed countries (LDCs) are permitted to introduce measures that deviate from the NTO clause for specified time periods in light of their institutional and administrative capabilities, financial or trade needs, or stages of development. Ghana and Angola are among the LDC WTO members for which the NTO clause has been waived in relation to local content requirements. Equatorial Guinea, Kazakhstan, Russia, Angola, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Indonesia, and Nigeria have translated their local content requirements into regulations and legislation (Esteves et al., 2013). On February 19, 2014, Ghana also translated its local content and local participatory requirements into a regulation.

Tordo et al. (2013) identified three broad categories of LCPs that support the recruitment and development of indigenous people in oil producing countries. These categories are:

- LCPs designed to increase the relative and/or absolute numbers of a nation’s indigenes employed by a foreign company. Angola, for example, has enacted Decree No. 5/95 mandating that foreign as well as national companies that employ more than five workers can only employ nonresident foreign workers if at least 70% of the workforce are Angolans (Tordo et al., 2013)

- LCPs that promote managerial skills and the development of higher technical capabilities among indigenes. For example, Ghana’s local content and local participatory regulation, L.I. 2204, stipulates that local content plans should be annually submitted by foreign petroleum companies to the Petroleum Commission of Ghana for approval. Similar to Ghana’s L.I. 2204, Article 6 of Azerbaijan’s Petroleum Sharing Agreement for the Shah Deniz Prospective Area, signed by BP and the state oil company, stipulates that before the commencement of oil field development, 30–50 % of professionals and 70% of nonprofessionals are required to be indigenous employees. Moreover, Article 6 stipulates that 70% and 85% of indigenous professional and nonprofessionals, respectively, are required to be employed upon commencement of oil and gas production (Tordo et al., 2013). Five years after oil and gas production has commenced, Article 6 stipulates that 90% and 95% of professionals and nonprofessionals, respectively, should be indigenous.

- LCPs designed to restrict the number of foreign employees and their duration of employment. According to Tordo et al. (2013), this category of LCP is designed to promote recruitment and career progression within an indigenous workforce. Angola’s Decree No. 6/10 stipulates that recruitment of expatriate workers can only occur when it is confirmed that no indigenous Angolan personnel are available who are adequately qualified to perform the job (Tordo et al., 2013). Moreover, the same decree restricts the contracts of nonresident foreigners to 3 years and allows the issuance of temporary work permits to foreigners for less than three months upon obtaining the approval of the Angolan Labor Ministry Inspection Department.

Technical Capabilities of Indigenous Ghanaians in Relation to the Requirements of the Offshore Industry

The upstream petroleum industry requires employees with specialized job skills. However, Otoo et al. (2009) found that because of the capital intensiveness of the upstream oil and gas sector, only a few highly skilled professionals were able to procure employment. According to Esteves et al. (2013), lack of capacity building to enable indigenes to meet job requirements constitutes the main constraint to human resource local content within the petroleum sector of developing countries. Therefore, at the outset of oil production in developing countries, there is a need to train indigenous people to enable them to occupy various positions within the upstream petroleum sector. The discovery in 2007 of substantial oil and gas stocks at the Jubilee field, and the significant oil production that commenced from November 2010, led to the sponsorship of a considerable number of indigenous Ghanaians to study courses related to oil and gas production through the GETFund.

The EDC was established by the ministries of power, petroleum, and trade and industry to enable indigenous SMEs to avail of numerous business opportunities within the Ghanaian upstream sector (EDC, 2013). Implementing capacity building programs for Ghana’s upstream petroleum sector falls within the EDC’s mandate. According to the EDC (2014), most SMEs and individuals seeking to participate in the Ghanaian upstream petroleum sector lack an understanding of activities related to oil and gas fields. This view is also supported by the finding of the Petroleum Commission that most indigenous companies, as well as individuals, are ignorant of the competencies required to meet demands within the Ghanaian upstream petroleum sector (Reporting Oil and Gas Project, 2014). Thus, there is the need to train individuals and SMEs wishing to participate in Ghana’s upstream sector.

Within the L.I. 2204 regulation, technical staffs are defined as engineers, technicians, and geoscientists. For over 40 years, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) has been producing engineers and technicians in the fields of electrical and instrumentation, mechanical, chemical, and civil engineering. To prepare indigenes for employment associated with Ghana’s significant oil find in 2007, KNUST and the University of Ghana introduced academic programs in petroleum engineering and geoscience, respectively. The 10 regional polytechnics in Ghana also train electrical and mechanical technicians. Accredited private universities in Ghana, notably, Reagent, All Nations, and KAAF Universities produce engineers as well. Moreover, there are vocational training schools scattered across Ghana that equip indigenes with practical, mechanical, and electrical technical skills. Because the upstream petroleum sector is a specialized field, all of these locally trained engineers, technicians, and geoscientists require further practical training that is specific to engineering and construction in the oil and gas fields to enable them function effectively.

The Jubilee Training Centre (JTTC) is a US $6 million project established by Jubilee oil field partners to provide academic and practical training for indigenes in the areas of instrumentation, process, mechanical, and electrical engineering for the upstream petroleum sector (Ghana Exploration and Production [E&P] Forum, 2013). The Jubilee field partners are Tullow Oil PLC, Kosmos, Anadarko, Sabre Oil and Gas, and GNPC. Of these partners, GNPC is the only company that is indigenously owned. The hazardous environment of the offshore petroleum sector requires specialized training of personnel before they can commence working. According to the Ghana E&P Forum (2013), JTTC offers competency courses and certification in subjects that include abrasive wheels, basic hand tools, electrical and installation techniques, electrical safety, fitting for non-fitting personnel, the theory and application of instrumentation techniques, measurement and control, the National Examination Board in Occupational Safety and Health (NEBOSH) the international general certificate, plant utilities, process safety, and NVQ Level II courses in process, mechanical, electrical, and instrumentation engineering. Thus, the establishment of JTTC has been a step in the right direction, as it builds the capacities of indigenous Ghanaians to take up jobs in the upstream petroleum sector.

To enable indigenous Ghanaians to develop technical skills in welding and fabrication, MODEC has established a US $1.6 million welder training center at Regional Maritime University to train, qualify, and certify welders for Ghana’s upstream petroleum sector. This training school is the first of its kind in the West African sub-region. Its welding and fabrication courses will equip indigenous Ghanaians with the necessary skills and certifications required to take up relevant jobs in the oil and gas fields.

Relevance of Training Courses Undertaken by Indigenous Ghanaian Students to the Skills Requirements in the Offshore Industry

The relevance of the sponsored courses to the advanced skills requirements in the oil and gas industry has been questioned by players within this industry. According to GETFund (2012), 86% of the selected indigenous Ghanaians were sponsored to undertake oil and gas management courses. Because the oil and gas sector is a highly specialized area, there is a widely held perception that these courses undertaken by indigenous Ghanaians are not relevant to the requirements of the various job positions available within the upstream petroleum sector. Thus, there is a need to establish the extent to which the training acquired by indigenous Ghanaians seeking jobs in Ghana’s oil fields affects the prevalent local content in its offshore petroleum industry.

Measurement of Human Resource Local Content

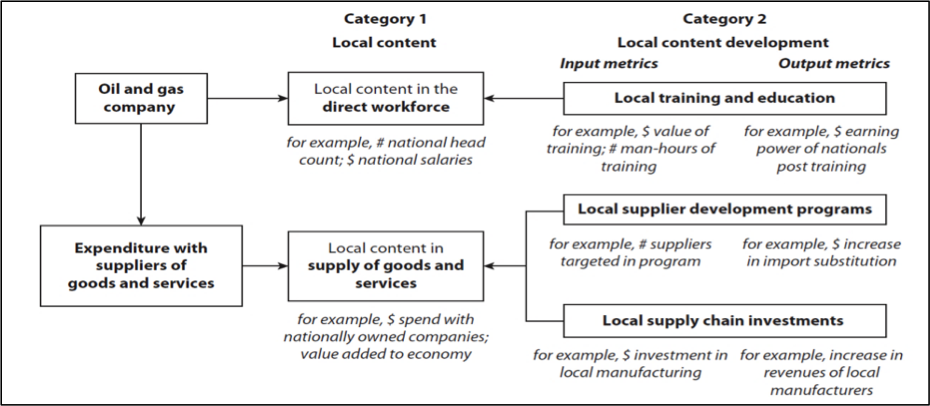

Human resource local content is defined within L.I. 2204 as the percentage of indigenous personnel within the petroleum industry value chain that can be measured in monetary terms. This definition reveals that Ghana’s petroleum LCP does not specify the metric. As shown in Figure 1, there are various categories of metrics for measuring local content. Consequently, an appropriate metric was required to measure Ghana’s petroleum human resource local content and to compare it to the requirements of L.I. 2204.

Figure 1. Local content categories of metrics in the oil and gas sector (source: World Bank, 2013).

Table 1 below shows that local content can be measured using different metrics. Tordo et al. (2013) identified two broad categories of measuring and performance reporting metrics for human resource local content. Measurement of the number of indigenous staff as a proportion of total FTE employees is the most popular metric used for measuring human resource local content within the direct workforce of a multinational petroleum company. The first metric is the extent to which indigenous employees of an oil producing company can capture labour expenditure by petroleum companies. An example would be headcounts of local employees within a multinational petroleum company. The second metric is efforts made by a government to increase its share of the human resource local content in the petroleum industry over time by building indigenous skills through the provision of appropriate training and education.

Table 1: Sources of Required Data, Reporting Process, and the Confidence Level in the Reported Local Content

|

Metric |

Key feature |

Information source |

Supply chain penetration |

Stage of procurement |

Expenditure category |

Confidence in data |

Simplicity to administer |

|

# FTE national citizens employed as % of total |

Head count |

Human resources data |

n.a |

n.a |

OPEX |

Good |

Simple |

|

# FTE national citizens in senior, supervisory, and skilled positions (or other job or grade disaggregation) |

Head count by job type |

Human resources data |

n.a |

n.a |

OPEX |

Moderate |

Simple |

|

# man-hours of national labor per year |

Man-hours |

|

n.a |

n.a |

OPEX |

Good |

Simple |

|

$ value of wages, benefits and social taxes paid to FTE national citizens employees as % of total |

Wages |

Human resources data |

n.a |

n.a |

OPEX |

Good |

Moderate |

|

$ value of wages, benefits and social taxes paid to FTE national citizens in senior, supervisory and skilled positions (or other job or grade disaggregation), as % of total |

Wages by job type |

Human resources data |

n.a |

n.a |

OPEX |

Moderate |

Moderate |

|

$ value of wages, benefits and social taxes paid to FTE national citizens employed and $ value of social taxes and expenses paid to expats, as % of total |

National wages and expat expenses/ taxes |

Human resources data |

n.a |

n.a |

OPEX |

Good |

Moderate |

Note. Metric for measuring local content. From the World Bank (2013).

Methodology

Research Approach and Design

A cross-sectional quantitative research survey was considered appropriate for the study. According to Randall et al. (2011), a cross-sectional survey design enables inferences to be made about a desired population at a particular point in time through the collection of data. Fowler (2013) observed that data collated from surveys, aside being preferable to data from other sources, are also able to meet the requirement for data that are unavailable elsewhere.

A quantitative research strategy facilitates the establishment of what transpires during a process of change, providing a specific direction for the implementation of a study (Buckley, 2015). L.I. 2204 was enacted to facilitate the establishment of a quota of indigenous employees within Ghana’s upstream petroleum industry. To determine whether the requirements stipulated by L.I. 2204 were being adhered to by multinational oil and gas companies operating in Ghana’s oil fields, this quantitative research strategy was used to determine the extent of differences between the prevalent human resource local content and the requirements of L.I. 2204 in Ghana’s offshore petroleum industry.

Population and Sample Selection

The population for the study was drawn from two multinational petroleum companies whose oil and gas development plans have been approved by the Petroleum Commission of Ghana.

In this study, stratified sampling, which entails first dividing the elements of a population into relevant subgroups or strata and subsequently drawing a sample from within each subgroup (Fowler, 2013), formed the basis of the sampling strategy. This sampling method was selected, because human resources within Ghana’s upstream petroleum sector are categorized into management, technical, and other staff. This categorization is also found in Ghana’s local content and local participatory regulation, L.I. 2204. To adequately cover the human resource requirements of L.I. 2204, and to ensure adequate representation of the entire population under study, the sample frame was grouped into management, technical, and other staff.

To determine the required sample size for this study, G*Power analysis was conducted using G*Power version 3.1. 9.2. The required sample size of 159 was obtained using three predictors, a medium effect size of 0.25, a power of 0.8, and three groups. A sample comprising 159 participants was drawn from the two selected multinational oil companies. The total permanent workforce of the selected two multinational petroleum companies was 379 comprising both locals and expatriates.

Measures and Assessment of Research Variables

A questionnaire using a seven-point Likert-type scale was used for the survey questions relating to the prevailing local content in Ghana’s upstream petroleum industry. The survey questions were grouped into five main sets, with each set focusing on the extent to which the independent variable had an effect on the dependent variable.

Data Collection Method and Analysis

Due to the virtual nature of the upstream petroleum industry, data was collected through a web-based survey. Saari and Scherbaum (2011) reported that over the past decade, web-based surveys have emerged as the preferred survey instrument for collating psychometric and other related data. In the social and behavioural sciences, the web-based survey offers enormous benefits to researchers, especially those engaged in employment-related surveys (Saari & Scherbaum, 2011).

Survey Monkey, which is an online survey tool, was used to administer surveys conducted with each of the six groups to collate data. The survey was distributed to participants through their private emails. The data obtained from the survey were inputted into IBM’s Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) to develop an understanding of the demographics of all the variables descriptive statistics using SPSS were obtained. Means, variances, and standard deviations were computed for all of the variables, indicating the characteristics of each variable.

Reliability Assessment and Validity

For the purpose of this study, Cronbach’s coefficient alpha was used to test the reliability of scale. Bonett and Wright (2015) indicated that when measurements relate to multiple questionnaires or test items, Cronbach’s alpha is considered a measure of internal consistency reliability. Hence, in this study, which employed multiple questionnaires as the measurement instrument, I determined that the closer the value of Cronbach’s alpha was to 1, the more reliable would be the scale with associated improvement of the internal consistency of the scale.

Pilot Study

The main study was preceded by a pilot study involving nine participants. The key objective of this pilot study was to collect feedback on the structure of the survey and to assess the clarity of the questions. A further objective was to test the reliability of the 7-point Likert-type scale using Cronbach’s coefficient alpha to measure the internal consistency between items in the scale. Criteria identified by George and Mallery (2003) were used to measure the internal consistency of the scale. The reliability of Cronbach’s alpha values was interpreted as follows: “≥ 0.9 – Excellent, ≥ 0.8 – Good, ≥ 0.7 – Acceptable, ≥ 0.6 – Questionable, ≥ 0.5 – Poor, and ≤ 0.5 – Unacceptable” (George & Mallery, 2003, p. 231). As shown in Table 5, the overall reliability of the scale in the pilot study was 0.799, which was considered good.

Table 2: Reliability Statistics for the Pilot Study

|

Cronbach’s alpha |

Cronbach’s alpha based on standardized items |

No. of items |

|

.799 |

.812 |

11 |

As shown in Table 2, when specific local content variables were deleted from the scale, Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.745 to 0.852, indicating acceptable to good reliability. Based on the outputs of item-total statistics, there was no need to eliminate any of the items in the scale. The scale was also reviewed by an expert panel to enable improvements to be made to the construct validity.

In this study, because of the appropriateness of the selected quantitative cross-sectional survey design as the data collection technique, validity of this design for investigating the prevailing local content in Ghana’s offshore petroleum industry was achieved.

Result

Descriptive Statistics

A total of 97 participants completed this survey. Thus, the survey response rate was 61% in relation to the required sample size of 159 participants. Out of the 97 participants who responded, 26 were management staff, 37 were technical staff, and 34 were other staff. The overall reliability for scale in the pilot study was 0.799, which was considered good. The descriptive statistics presented in Table 2 indicate that the mean value for each of the management and technical staff groups regarding their opinions on the extent to which the overall prevailing local content meets the requirements of L.I. 2204 was 5.4. The mean value for the other staff group was 5.5. This range of means between 5 and 5.5 indicated that the management, technical, and other staff were “somewhat agreed” that the prevailing local content meets the requirements of L.I. 2204. Descriptive statistics also provided insights on participants’ opinions concerning the extent to which the training acquired by indigenous Ghanaians seeking jobs in Ghana’s oil fields affects the prevailing local content. The mean value for the management staff group was 5.8, while the mean value for each of the technical staff and the other staff groups was 5.6. This range of means between 5.5 and 6 indicated that the management, technical, and other staff groups “agreed” that the training acquired by indigenous Ghanaians seeking jobs in Ghana’s oil fields affects the prevailing local content in its offshore petroleum industry.

Table 3: Descriptive Statistics Obtained for the Survey

|

|

N |

Mean |

Std. dev.

|

Std. error |

95% confidence interval for mean |

Min. |

Max. |

|

|

Lower bound |

Upper bound |

|||||||

|

Prevalent management staff local content |

Mgt._staff |

26 |

5.1923 |

1.02056 |

.20015 |

4.7801 |

5.6045 |

4.00 |

|

Tech_staff |

37 |

5.3514 |

.91943 |

.15115 |

5.0448 |

5.6579 |

4.00 |

|

|

Other_staff |

34 |

5.1176 |

.97746 |

.16763 |

4.7766 |

5.4587 |

4.00 |

|

|

Total |

97 |

5.2268 |

.96291 |

.09777 |

5.0327 |

5.4209 |

4.00 |

|

|

Prevalent technical staff local content |

Mgt_staff |

26 |

5.2692 |

1.25085 |

.24531 |

4.7640 |

5.7745 |

3.00 |

|

Tech_staff |

37 |

5.4865 |

.98943 |

.16266 |

5.1566 |

5.8164 |

3.00 |

|

|

Other_staff |

34 |

5.5000 |

1.18705 |

.20358 |

5.0858 |

5.9142 |

2.00 |

|

|

Total |

97 |

5.4330 |

1.12645 |

.11437 |

5.2060 |

5.6600 |

2.00 |

|

|

Prevalent other staff local content |

Mgt_staff |

26 |

6.1154 |

.71144 |

.13953 |

5.8280 |

6.4027 |

5.00 |

|

Tech_staff |

37 |

6.0270 |

.72597 |

.11935 |

5.7850 |

6.2691 |

5.00 |

|

|

Other_staff |

34 |

6.1176 |

.76929 |

.13193 |

5.8492 |

6.3861 |

5.00 |

|

|

Total |

97 |

6.0825 |

.73130 |

.07425 |

5.9351 |

6.2299 |

5.00 |

|

|

Prevalent overall staff local content |

Mgt_staff |

26 |

5.3846 |

.69725 |

.13674 |

5.1030 |

5.6662 |

4.00 |

|

Tech_staff |

37 |

5.4324 |

.64724 |

.10641 |

5.2166 |

5.6482 |

4.00 |

|

|

Other_staff |

34 |

5.5294 |

.78760 |

.13507 |

5.2546 |

5.8042 |

4.00 |

|

|

Total |

97 |

5.4536 |

.70741 |

.07183 |

5.3110 |

5.5962 |

4.00 |

|

Before conducting the one-way ANOVAs, the assumption of normality was tested by applying skewness and kurtosis tests as well as histograms. The results of the skewness and kurtosis tests for all dependent variables fell within a range of -1 and +1, indicating that the assumption of normality held. The results of these tests are shown in Table 3.

Table 4: Skewness and Kurtosis Tests Result

|

|

Prevalent management staff local content |

Prevalent technical staff local content |

Prevalent other staff local content |

Prevalent overall staff local content |

Acquired management skills training effect on local content |

Acquired technical skills training effect on local content |

Acquired other skills training effect on local content |

Locals’ acquired training effect on local content |

|

|

N |

Valid |

97 |

97 |

97 |

97 |

97 |

97 |

97 |

97 |

|

Missing |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Skewness |

.170 |

-.566 |

-.129 |

.348 |

-.733 |

-.436 |

-.173 |

-.360 |

|

|

Std. error of skewness |

.245 |

.245 |

.245 |

.245 |

.245 |

.245 |

.245 |

.245 |

|

|

Kurtosis |

-1.016 |

.288 |

-1.101 |

-.103 |

1.180 |

-.285 |

.220 |

-.100 |

|

|

Std. error of kurtosis |

.485 |

.485 |

.485 |

.485 |

.485 |

.485 |

.485 |

.485 |

|

Results of the One-way ANOVA

The results of this ANOVA showed that there were no statistically significant differences between these three staff groups at a level of p > 0.5 for any of the dependent variables. The results of the one-way ANOVA are summarized in Table 5.

Test Results for Hypothesis 1

H1o: µManag_Staff_LC = µTech_Staf_LC = µOther_Staff_LC. The prevailing human resource local content does not differ from the requirements of Ghana’s petroleum local content regulation in its upstream petroleum industry.

H11: At least two means (µk) are not equal. The prevailing human resource local content does differ from the requirements of Ghana’s petroleum local content regulation in its upstream petroleum industry.

The results of the analysis indicated that the management, technical, and other staff were somewhat agreed that the prevailing human resource local content does not differ from the requirements of Ghana’s petroleum local content regulation. Differences in the means obtained for management, technical, and other staff groups regarding their opinions on the extent of differences between the prevailing human resource local content and the requirements of Ghana’s petroleum local content regulation were not statistically significant at the p > 0.05 level for the three conditions, F(2, 94) =.331, p = .719. As differences in the means were not statistically significant at the p > 0.05 level, the null hypothesis was not rejected. Thus, in response to RQ1, the prevailing human resource local content somewhat meets the requirements of L.I. 2204.

Table 5: Summary of the Results of the One-way ANOVA

|

|

|

Sum of squares |

df |

Mean square |

F |

Sig. |

|

Prevalent management staff local content |

Between groups |

1.010 |

2 |

.505 |

.539 |

.585 |

|

Within groups |

88.000 |

94 |

.936 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

89.010 |

96 |

|

|

|

|

|

Prevalent technical staff local content |

Between groups |

.956 |

2 |

.478 |

.372 |

.691 |

|

Within groups |

120.859 |

94 |

1.286 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

121.814 |

96 |

|

|

|

|

|

Prevalent other staff local content |

Between groups |

.184 |

2 |

.092 |

.169 |

.845 |

|

Within groups |

51.156 |

94 |

.544 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

51.340 |

96 |

|

|

|

|

|

Prevalent overall staff local content |

Between groups |

.336 |

2 |

.168 |

.331 |

.719 |

|

Within groups |

47.706 |

94 |

.508 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

48.041 |

96 |

|

|

|

This quantitative cross-sectional study was aimed at determining the extent to which the prevailing human resource local content meets the requirements of L.I. 2204 in Ghana’s upstream petroleum industry. Moreover, it was aimed at ascertaining the extent to which the training acquired by indigenous Ghanaians seeking jobs in Ghana’s oil fields affects the prevailing local content in its upstream petroleum industry. The findings of this study suggest that differences in the means of the management, technical, and other staff groups regarding their opinions on the extent of differences between prevailing human resource local content and the requirements of L.I. 2204 were not statistically significant at the p > 0.05 level for the three conditions, F(2, 94) =.331, p = .719.

Recommendations

The perceived lack of jobs available within Ghana’s upstream oil and gas sector has been attributed to the inability of politicians and the Petroleum Commission of Ghana to ensure that multinational petroleum companies are committed to the employment of locals. The findings of a study entailing a critical examination of livelihoods capitals relating to the job situation, conducted by Ramos-Mrosovsky (2012), revealed that the jobs promised by the government following the inception of oil production were simply not available.

Steps should be taken by the leaders of multinational petroleum companies and the Petroleum Commission of Ghana to create awareness among indigenous Ghanaians that the prevailing local content meets the requirements of L.I. 2204 in Ghana’s upstream oil and gas industry. Further, leaders of the Petroleum Commission should take pragmatic steps to inform indigenous Ghanaians that the human resource requirements of L.I. 2204 relating to management, technical, and other staff positions within the upstream oil and gas industry are being met by Ghanaians with relevant and specialized skills.

Further, once indigenous Ghanaians are informed regarding the expertise required by multinational oil companies, they can take the necessary steps for acquiring the requisite skills to compete with expatriates for positions within Ghana’s upstream oil and gas sector. In addition, there is the need for multinational oil companies to institute reasonably accessible training programs at affordable prices. GETFund personnel should be well informed when granting scholarships for studies that are relevant to the skills required in the upstream oil and gas industry.

Limitations of the Study

This study entailed several limitations. First, because of the confidential nature of administrative procedures in the offshore industry, the selected multinational oil and gas companies were unwilling to release detailed financial information on their human resources. This information was required to determine the prevailing local content in monetary terms. According to Tordo et al. (2013), if the human resource local content metric emphasizes the share of total gross salaries paid to indigenous employees, then multinational petroleum companies will be forced to establish a comprehensive succession plan program that ensures that indigenes are recruited and trained to take up higher paying positions entailing advanced skills. Second, the generalizability of this study was limited as only two multinational oil companies whose oil and gas development plans have been approved by the Petroleum Commission of Ghana were selected for the survey. Third, out of the 159 participants sampled for this study, 97 responded, resulting in a response rate of 61%.

Author: Papa Benin, Ph.D.

References

Atsegbua, L. (2012). The Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry Content Development Act 2010: An examination of its regulatory framework. OPEC Energy Review, 36(4), 479-494. doi:10.1111/j.1753-0237.2012.00225.x

Bonett, D. G., & Wright, T. A. (2015). Cronbach’s alpha reliability: Interval estimation, hypothesis testing, and sample size planning. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(1), 3-15. doi:10.1002/job.1960

Buckley, A. P. (2015). Using sequential mixed methods in enterprise policy evaluation: A pragmatic design choice? Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 13(1), 16-26. Retrieved from http://www.ejbrm.com/issue/download.html?idArticle=395

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the interval structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297-334. doi:10.1007/BF02310555

Egwaikhide, F. O., & Omojolaibi, J. A. (2014). A panel analysis of oil price dynamics, fiscal stance and macroeconomic effects: The case of some selected African countries. Retrieved from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-Panel-Analysis-of-Oil-Price-Dynamics-Fiscal-Omojolaibi-Egwaikhide/576c9185490ead5899f860f0b9c27b9f99e785e0

Enterprise Development Centre, Ghana. (2013). The role of EDC. Retrieved from http://www.edcghana.org/index/about

Enterprise Development Center Ghana. (2013, December 9). Local content policy for the oil and gas sector gains grounds - Ghanaian SME Hydra Offshore signs MOU with Wood Group PSN. Retrieved from http://www.edcghana.org/uploads/news/EDC local Content Initiative.pdf

Esteves, A. M., Coyne, B., & Moreno, A. (2013, July). Local content initiatives: Enhancing the subnational benefits of the oil, gas and mining sectors. Revenue Watch Institute. Retrieved from http://www.revenuewatch.org

Fowler, F. J. (2013). Survey research methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ghana Education Trust Fund. (2014). History of GETFund. Retrieved from http://www.getfund.gov.gh/index.php/2013-05-09-10-08-27/2013-05-09-10-39-06

Ghana Exploration and Production Forum. (2013). Jubilee Technical Training Centre (JTTC) opens in Ghana. Retrieved November 10, 2015, from http://gh-epf.org/index.php/94-industrial-news/239-jubilee-technical-training-centre-jttc-opens-in-ghana

Ghana National Petroleum Corporation. (2014, May 13). History of exploration in Ghana. Retrieved from http://www.oilandgasirc.org.gh/page.php?id=0029&pgtid=3&cntid=rart&pd=3&td=rart&tsid=8&p=Articles

Gray, D. (2013). Local content challenges vex Brazil’s offshore operators. Offshore, 73(11), 64-66. Retrieved from http://www.offshore-mag.com/articles/print/volume-73/issue-11/brazil/local-content-challenges-vex-brazil-s-offshore-operators.html

Independent Oil and Gas Information Resource Center. (2015, September 4). Comply with local content law or face sanctions - oil, gas companies cautioned. Retrieved from http://oilandgasirc.org.gh/page.php?id=0000000838&pgtid=3&cntid=newinfo&pd=3&td=newinfo&tsid=9&p=News

Jensen, J., & Tarr, D. (2008). Impact of local content restrictions and barriers against foreign direct investment in services. Eastern European Economics, 46(5), 5-26. doi:10.2753/EEE0012-8775460501

Mwakali, J. A., & Byaruhanga, J. N. M. (2011). Local content in the oil and gas industry: Implications for Uganda. In J. A. Mwkali and H. M. Alinaitwe (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Advances in Engineering and Technology, Entebbe, Uganda, 31 January–1 February 2011 (pp. 517–522). Kampala, Uganda: Macmillan Uganda Publishers.

Oil and Gas IQ. (2015). Local content for oil & gas: Is it actually working? Retrieved from http://www.oilandgasiq.com/gas-oil-production-and-operations/white-papers/local-content-for-oil-gas-is-it-actually-working/

Otoo, K., Osei-Boateng, C., & Asafu-Adjaye, P. (2009). The labor market in Ghana. Retrieved from http://www.ghanatuc.org/The-Labour-Market-in-Ghana.pdf

Petroleum Commission. (2015, August 15). Upstream operators in Ghana’s oil and gas industry. Retrieved from http://www.petrocom.gov.gh/upstream-operators.html

Randall, W. S., Nowicki, D. R., & Hawkins, T. G. (2011). Explaining the effectiveness of performance-based logistics: A quantitative examination. International Journal of Logistics Management, 22(3), 324-348. doi:10.1108/09574091111181354

Ramos-Mrosovsky, C. (2012). Can Ghana escape the ‘oil curse’? Africa Law Today, 4(1), 1-4. doi:10.1108/09574091111181354

Reporting Oil and Gas Project. (2014, September 23). Oil & gas: SMEs lack knowledge of industry. Retrieved from http://www.reportingoilandgas.org/oil-gas-smes-lack-knowledge-of-industry/

Saari, L. M., & Scherbaum, C. A. (2011). Identified employee surveys: Potential promise, perils, and professional practice guidelines. Industrial & Organizational Psychology, 4(4), 435-448. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9434.2011.01369.x

Tordo, S., Tracy B. S. & Arfaa N. (2011) National oil companies and value creation. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Tordo, S., Warner, M., Manzano, O., & Anouti, Y. (2013). Local content policies in the oil and gas sector. World Bank Publications

Ugwushi, B. I., Olabowale, O. A., Eloji K. N., & Ajayi C. (2011). Entrepreneurial implications of Nigeria's oil industry local content policy: Perceptions from the Niger Delta region. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 5(3), 223–241. doi:10.1108/17506201111156698